The Argentine journalist who was on the front lines of the battle in Ukraine

“I fell into the war almost by accident,” says Ignacio Hutin and a smile escapes him. He has a way of speaking that ranges from intimate to expansive enthusiasm, from concern to be understood to precision for data.

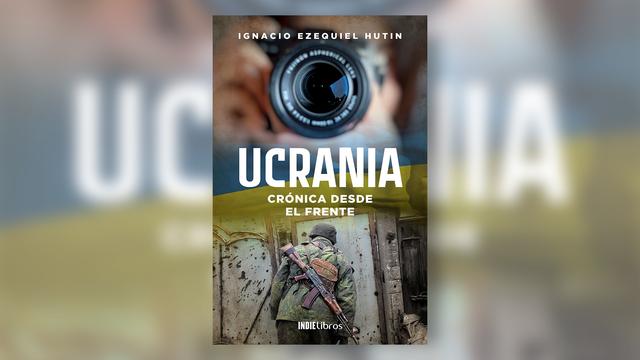

Thus he speaks and thus also writes: Hutin spent long months in Ukraine and in the territories that declared themselves independent: the Lugansk People's Republic and People's Republic from Donetsk, and recounted the war from within in the book Ukraine. Chronicle from the front, what exclusive content from Leamos.com.

These days, with the military escalation involving the United States, England and the other European countries aligned with NATO, On the one hand, and Putin's Russia on the other, Ukraine has become permanent news and the idea of global conflict looms as a disturbing possibility b>. But the truth is that the country has been at war since 2014. “What happens is that after the Minsk agreements,” says Hutin, “the war stagnated and somehow disappeared from the media. But I was interested in seeing not only what had happened with the war, but also with these two regions that declared themselves independent”.

Though not recognized by other nations, Donetsk and Lugansk have their own governments, their own institutions, their own flags and schools, and even their own soccer leagues. Two years before the war, Donetsk had hosted the Eurocup; a very modern airport and the second largest stadium in the country had been built there. “Donetsk is a city with more than a million inhabitants,” says Hutin. “It is as if Rosario, Córdoba or Mendoza ceased to be part of Argentina. Tomorrow, without any anticipation”.

News from the front lines

Ignacio Hutin arrived in Donetsk with the idea of writing for different international media what the present was like in these territories: how people lived, what the usual movement in the streets was like, what it was like to be a civilian in a warlike environment. But once in the city, a Spaniard made him see that there was no point in being there and not talking about the conflict.

In a haphazard but crucial way, that man became a fixer—someone who helps foreign journalists in war zones. “And he did it,” Hutin says, “simply because he was bored and he had time. He had already stopped working and, as a Spaniard, the only way to get out of there is via Russia, but for that you need a visa and being in Donetsk I couldn't get it”. It's that the Ukrainian government considers those who fight in the rebel armies — and all foreigners who join them — as terrorists. In fact, many combatants were imprisoned once they returned to their countries.

“There is a very famous case, a Brazilian named Marques Lusvarghi”, says Hutin. “In general, all the soldiers who join these brigades try to maintain a certain anonymity. It is not easy to find them on social networks, they use pseudonyms. But this Brazilian was extremely visible. He was taking photos all the time and showing himself on the networks, and he ended up in jail. He was ambushed: he was offered a job on the Black Sea. Ukraine is a country at war and the enemy has information. It's not a joke that you're going to jail on terrorism charges. Joining these brigades is a very important risk. I was very interested in knowing why Spaniards, Colombians, Brazilians, Chileans—I didn't meet any Argentines—are willing to fight in a completely alien war.”

The issue of alienation and belonging is a key to understanding the motivations of the inhabitants. One night, Hutin visited a civilian bunker that was less than a hundred meters from where the armies were fighting. There were those who lived in that neighborhood before the war: they had stayed close to their homes with the idea that at some point they could return. Although the house was in ruins from the projectiles, the promise of return worked for them. “It's a very Russian idea,” he says, “which is not so different from what happened at Chernobyl, where a lot of people came back illegally.” Hutin confesses that, even with the rumor of the shots and the bombs, what scared him the most was the people who slept there: they are people who have been living underground for years and are very upset. "If you're going to stay all night," he says he was told, "take a knife."

—But you were also on the front lines. How did you get them to let you accompany the army?

—Thanks to that Spanish fixer. He put me in contact with foreigners who had fought in a left-wing internationalist brigade and, for this reason, unlike other brigades, they always accepted volunteers from other countries. When I wanted to go to this region, I did not ask the government of these breakaway republics for authorization, but I contacted the commander — his name was Alexey Markov; he died in 2020 supposedly in a traffic accident—and they took me everywhere. They even assigned me a guide, who was a guy from Latvia who spoke perfect English. One goes with the idea that he is going to meet a terrorist group, with Al Qaeda, with Bin Laden, and they were attentive, kind, courteous. All the while demonstrating to a journalist that they are not terrorists, that they are not bad. So much so, that the commander gave me a private interview of almost two hours and made a gesture that seemed very valuable to me. After those almost two hours, I turn off the recorder and he asks me what I thought of all this. I thought it was amazing: a guy who commands a brigade in the middle of a war asks someone who has nothing to do with what he thinks of the situation.

—What did you say?

—I told him that if I were from that region, I wouldn't mind being part of Ukraine, Russia, or an independent state. All I would like is for the war to end. The rest, we'll see later. It might not be the answer he was hoping for, but it was the most honest he could give.

—How is the work of a reporter on the battlefield with technology?

—I used social media a lot. They were key to meeting people. Without those contacts, I wouldn't have known what to do. At the front I did not have access to the internet and it was very difficult, not only because of the difficulties with the translations, but also because I did not have access to the information. I couldn't get contacts, I couldn't talk to anyone, I couldn't look things up. Internet access is key. There are areas where there is not even a telephone signal, because the telecommunications antennas were destroyed and without communication you cannot do anything.

The spark that started the fire

—To understand the conflict in Ukraine, can you think of Yugoslavia in the 1990s?

—Somehow yes, because the conflicts in Yugoslavia had to do with ethnic issues: the Serbs wanted to keep the territories where Serbs lived, the Croats too, and so on. But, on the other hand, Ukraine was a single republic within the Soviet Union. There is no record of ethnically Russians in Ukraine seeking independence, like Montenegro or Croatia. In that sense they are not comparable, although the polarization of identities, the ethnic, cultural, linguistic, religious, political division and others are part of the dispute.

—Independence movements in Europe tend to have cycles. I am thinking, for example, of the conflict in Catalonia.

—I was in Donetsk when Puigdemont declared and did not declare independence. I saw him live with the Spanish. It was a very curious situation: there were Spaniards from the right, from the left and also communists. It was very striking to see from Donetsk the difference they had with the issue of Catalonia. That said, I believe that the key difference between Catalonia and Donbáas —the disputed territory in Ukraine— is that, in Spain, at least in the last few centuries, there is no history of murders masses of Catalans for the mere fact of being Catalan.

—Who drives violence to such extremes in Ukraine?

—There are nationalist groups that murdered hundreds of thousands of civilians for the mere fact of not being Ukrainian. Not just Russians; also Poles, Jews. The most striking thing is that, to this day, these groups that fought on the Nazi side in World War II against the Soviet Union are claimed by the Ukrainian state. There are monuments to the leaders. A stadium named after one of them was recently inaugurated, which was called Roman Suhevic. If you are an ethnically Russian citizen of Eastern Ukraine and you see how the state that should represent and defend you vindicates and supports ultranationalist groups that carried out massacres against people like you, it makes some sense for you to take up arms. That is why I do not agree with the idea promoted by the Ukrainian state, that this is a mere invasion of Russia because Putin does not like Ukraine moving away from Moscow and closer to the European Union. It's a very simplistic idea. A war can never be explained by just one reason. There are many factors behind the war and part of this context is this background.

—You mention Putin and I must say that the figure of Putin makes one look at Ukraine with some sympathy. If there is a choice between Putin and an independent state, I side with the state.

—That is exactly what the United States says: that Ukraine is an independent country and, as such, has the right to choose its future.

—I guess if the future they chose wasn't close to them, they wouldn't be as open to self-determination.

—Sure. Ask Cuba when she decided to go for communism. I respect decisions when they suit me. But Russia is also like that. I think Putin is a very interesting figure. He is a nationalist, he is a leader of those who are everything and are nothing. It vindicates Russia's role as a power and, in some way, restored the national pride they had lost in the 1990s, during the era of Boris Yeltsin. In addition, during the first two presidencies —from 2000 to 2008—, the economy improved due to the price of hydrocarbons. You have a leader who restores your national pride, improves your pocket and, as if that were not enough, in all the opportunities that Russia had to show that it is becoming a power again, it succeeded: in Georgia, in Chechnya, perhaps it did not succeed in Ukraine but “regained” – and I mean that in terms of the Russian state, because that's the word they use – the Crimean peninsula.

Modern warfare and the globalized economy

—In a perhaps excessive comparison, is Putin to Boris Johnson what Galtieri is to Thatcher? I tell them because of how Johnson, who is being questioned so much, clings to Putin's military movements to recover a positive image.

—I agree. Because it is also not just the theme of the party and that he has come out dancing in the middle of the strictest quarantine. It also has to do with Brexit. The UK is increasingly isolated. Brexit has proven to be a lousy policy and they are suffering not only in the British Isles but also in places like Gibraltar and the Malvinas. Boris Johnson is being questioned a lot and is increasingly isolated. It is no coincidence, then, that he was the leader of a NATO member country that most supported the United States with respect to Ukraine. The United States said that there could be an invasion and that Ukraine had to be supported with arms, money and troops. Germany did not send troops or weapons; Neither did France. In Spain it is being debated. The only one who supported the United States was Boris Johnson. I think that this has to do with urgently seeking an ally, otherwise the United Kingdom would be too isolated.

—How does the conflict in Ukraine affect Argentines?

—In principle, Argentina is affected in a very direct way, because Ukraine is an exporter of agricultural products, especially wheat. Western Ukraine is supposed to be the most fertile area in Europe and a lot of wheat is produced. With the escalation that we have seen in recent days, the international price of wheat has increased a lot and this, in some way, is good for Argentina. On the other hand, everything that happens in this region will affect the global economy. Russia is going through a difficult economic situation. It sounds strange to say it from Argentina, but Russia has very high inflation, which is close to 7% per year. This has to do not only with the drop in the price of hydrocarbons, but with the trade sanctions imposed after the annexation of Crimea and the alleged unofficial support given to Ukrainian separatists. In this sense, if suddenly more sanctions are applied and Russia cannot export gas to the European Union, it will affect all markets.

READ MORE